Definition of antibody: any

of a large number of proteins of high molecular weight that are

produced normally by specialized B cells inside an individual's body after stimulation by an outside antigen and that act specifically against this antigen in an immune response to the benefit of the individual

Definition of autoantibody: an antibody active against a tissue constituent of the individual producing it

Every so often I am encouraged to fight or at least make peace with this autoimmune disease. Best intentions etc. I am not complaining and I've long stopped responding. Generally, people mean well.

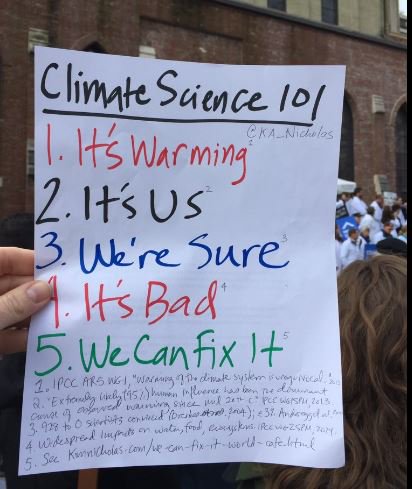

One of the perks of working in a medical research facility is that from time to time I get to watch the experts when they check my blood samples. Most of the routine parameters are done by machines, a long line of humming equipment, robots, but the tricky ones, like autoantibodies, have to be assessed in person by at least two people. It's a complicated process of sample dilution and electronic microscopy and control tests and seriously, I haven't the slightest idea how it actually works.

First the shock of realising that these light and dark green blobs displayed on a large monitor in a darkened room are actually incredibly minute parts of my white blood cells and that the two people in the room with me can determine my state of health - at least one aspect of it - by looking at them.

Then the realisation that this is neither an alchemist's workshop nor a witch's coven. Nobody is whispering spells. Instead, careful observation, comparison, determination, measurement. But my blood, nevertheless.

It can be almost uplifting to watch, to follow the cursor outlining edges and highlights. My blood. And yet, I am still at a loss. Where others see proof, I see green blobs. (BTW, this image is not of my actual blood, it's a training picture.)

I had a hard time with some of the childhood illnesses. To some of the experts this is yet another indication of something or other connected with an autoimmune predisposition. Not that it helps.

When I was eight years old, I caught a triple whammy (mumps, chicken pox and croup) and - so the story goes - was ill for weeks. When it was suggested that I should be in hospital, my mother did her not-over-my-dead-body act and as a result, an elderly doctor, a friend of the family, would come every evening with his elderly wife to administer an injection of penicillin. The elderly wife was meant to calm me with story telling and singing of songs. To this day I have a vivid image in my mind of me kicking and screaming with a hoarse voice while several arms are holding me down.

I recovered. Walking was hard at first. I was a skinny rat and needed a strong hand to hold on to for a short while. This of course has long become part of my family's folklore, at times used to highlight my weakness, other times, my strength and above all, my mother's despair and dedication.

When I was 16, I got the measles. It was quite embarrassing when my boyfriend-at-the-time looked at my face and said, yuk. That was on the evening of a trip to Berlin. I had won this trip in an essay competition. At the time, every teenager worth their wild dreams wanted to go to Berlin and mix with the anti-establishment crowd. But trips to Berlin were complicated in the cold war years of the 1970s. Berlin was a fortified, divided city under the administration of the four allied forces who won WWII. Getting there involved permits and lots of regulations from vaccines to hard currency and most importantly, a neat appearance both in real life and on the passport picture, then a slow bus journey on one of the transit corridors cutting through East Germany and long hours of border checks.

It was deemed important for all Germans to somehow be connected to Berlin and the authorities, German and allied, came up with all sorts of ideas to entice the right people to visit and defy the image of West Berlin being a beleagered slice of a city surrounded by an iron curtain.

In my family, it was a difficult and emotional subject because, while she had family and history in Berlin, my mother could not get a permit to travel. This had to do with the infamous Lastenausgleich, a post WWII programme intended to recompense for material losses, e.g. my mother's childhood home in East Berlin, but opening badly healed scars and considered fraught and unfair by many incl. my mother. Long story.

Winning this essay contest was a bit of balm on my mother's wounded soul. So to speak. And I messed it up. As usual.

The boyfriend-at-the-time had come to see me off to Berlin, somewhat jealous, and in view of my glaringly obvious unfit state he quickly spread the news that not even a prize winning essay could save me from looking like a rotting pumpkin.

So, the measles, followed immediately by pneumonia, kidney inflammation and gastritis. My mother moved me into my parent's bedroom and the entire family suffered from lack of sleep for the weeks it took me to recover. Also, I missed two exams but the glorious essay saved me from having to resit. I don't remember what the essay was about - nothing momentous - and the boyfriend fell by the wayside.

My point: I did fight. Then. These were battles I knew I could win provided I worked hard. On every level, even the cellular.

This one, no. I haven't a hope.

As for making peace, why? With whom, with what?

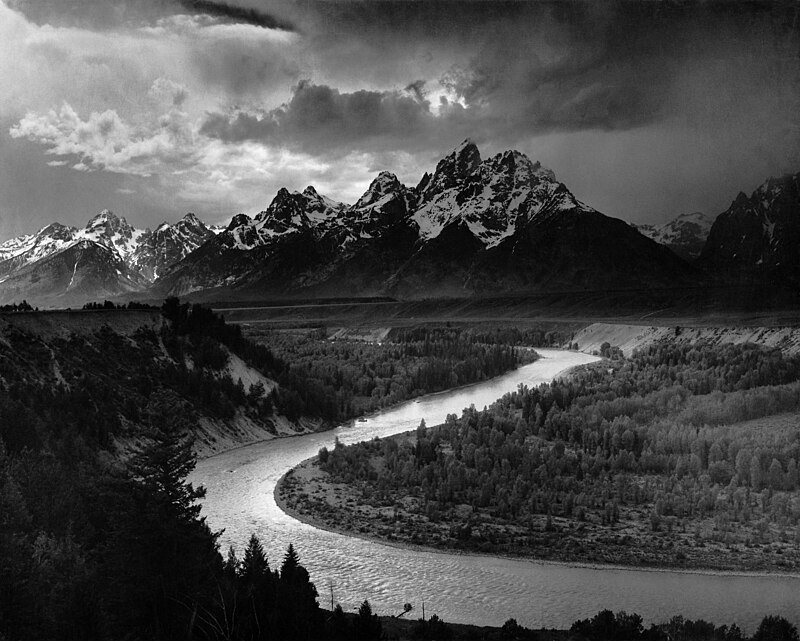

Instead, here I am, exhausted, searching for comfort looking out from the patio doors across the garden, peonies, roses, iris, a freshly cut lawn, all glorious in the sunshine.

I take a deep disciplinary breath and get on with it.